The board game Monopoly is one of the most iconic games of all time, known for its colorful money, intense family disputes, and infamous “Go to Jail” square. But beyond the rolling dice and building of empires, Monopoly has a history filled with surprising twists—including hard economic lessons, unintended consequences, and outright theft.

An Anti-Capitalist Origin Story

The game Monopoly as we know it today was born from an entirely different game—or at least different intentions. In fact, the game’s origins were rooted in social commentary on the pitfalls of capitalism and monopolies—far from the competitive “crush your family” themes often associated with it today.

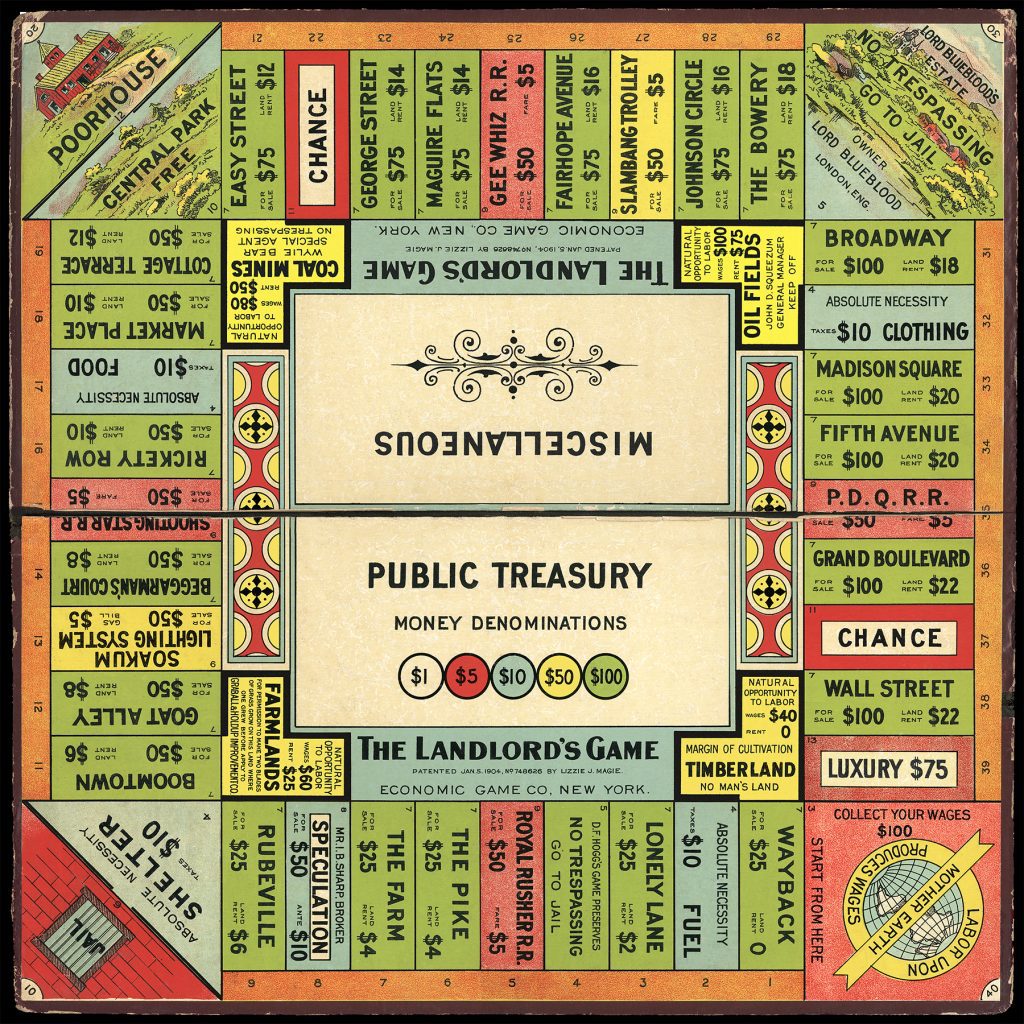

In 1904, an outspoken feminist named Elizabeth “Lizzie” Magie patented The Landlord’s Game, a board game designed to demonstrate the social and economic injustices of monopolies. Magie, an advocate of Henry George’s “single tax” theory, wanted to show how rent and land ownership could lead to the concentration of wealth and the impoverishment of the masses. “Let the children once see clearly the gross injustice of our present land system,” Magie wrote in 1902, “and when they grow up, if they are allowed to develop naturally, the evil will soon be remedied.”

The original game featured two sets of rules. In the “monopolist” version, players aimed to dominate and crush their opponents, while in the “prosperity” version, all players shared wealth. In 1923, Magie re-patented the game with modifications, including cardboard houses that increased rents when placed on properties.

The Darrow Do-Over

As Magie’s game spread informally through word of mouth—mostly among college kids, social clubs, and, oddly enough, Quakers—it was often the “monopolist” version that was favored. It was this version that a Philadelphia businessman named Charles Todd introduced to his friend, Charles Darrow, one night in 1932. That evening, Charles Todd, Charles Darrow, and their wives played several rounds of the game. Later, Darrow, impressed with the gameplay, asked the Todds to write down the rules.

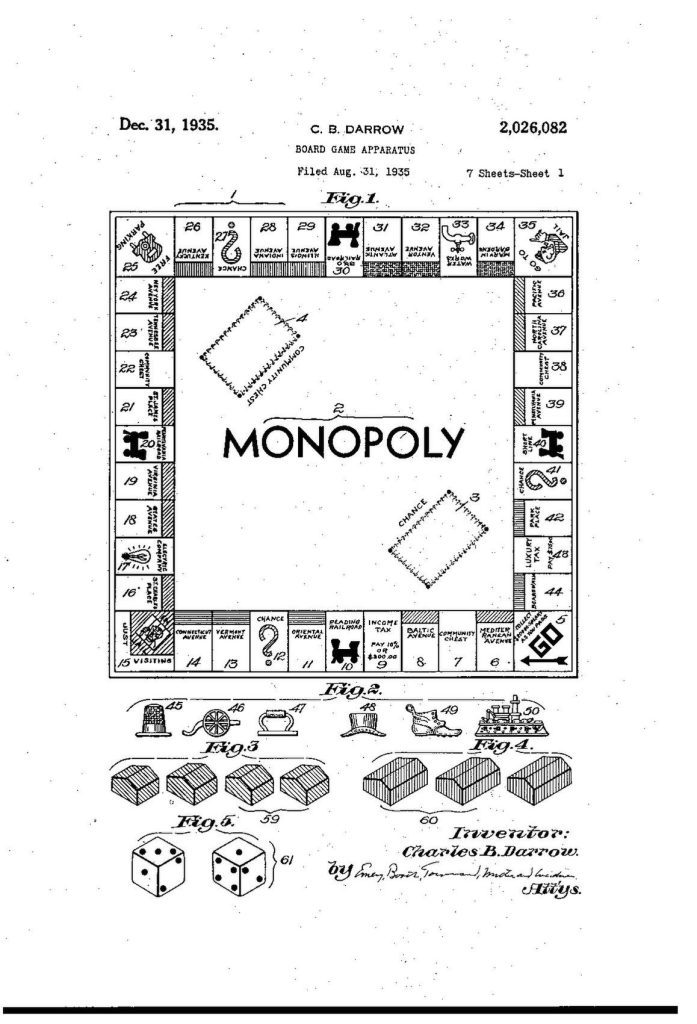

Darrow then took the game, modified it, and brazenly sold it to the Parker Brothers toy company as his own creation. Although Magie’s game laid the foundation, Darrow’s version—emphasizing competition and financial domination—became the version of Monopoly that we know today.

For decades, Darrow reaped the success of Monopoly while Magie’s role remained obscure. However, when Darrow’s Monopoly took off in the mid-1930s, Parker Brothers embarked on an effort to cover up the fact that their best-selling game was, in fact, in the public domain. So, they built…well…a monopoly on the game market by buying up the rights to other related games—including Magie’s original, The Landlord’s Game. Magie reportedly received $500 and no royalties for her patent to The Landlord’s Game and two other game ideas. She was initially excited, but soon after realized what had happened and became angry. In the mid-1930s, she gave multiple interviews to news outlets insisting that Darrow and Parker Brothers had stolen her idea. Darrow doubled down and insisted that the game was entirely his invention. When asked how he developed the game he told one reporter, “It’s a freak. Entirely unexpected and illogical.”

Monopoly’s Mass Appeal

By the mid-1930s, Monopoly was a smash hit in the United States. Perhaps because the country was still reeling from the Great Depression and a game centered around wealth accumulation was a form of escapism. Whatever the reason, the idea of buying property, collecting rent, and becoming rich—even in a fictional setting—resonated with players.

Over time, Monopoly grew beyond a simple pastime. Its iconic pieces, properties named after Atlantic City streets, and colorful play money became ingrained in popular culture. Versions of Monopoly have since been adapted for hundreds of cities, brands, and even entertainment franchises, making it a globally recognized symbol of competitive capitalism.

The Truth Emerges

Then, in 1973, economics professor Ralph Anspach published a game called Anti-Monopoly, a parody of the Parker Brothers game that critiqued capitalist monopolies and unintentionally recaptured the sentiment behind Magie’s version. Parker Brothers subsequently sued him for trademark infringement. While preparing his defense for the trademark infringement case, Anspach discovered the dark twist to Monopoly’s origin story—specifically how Monopoly had evolved from Lizzie Magie’s The Landlord’s Game into the version that Charles Darrow appropriated.

Anspach based his defense on the grounds that Monopoly had existed in the public domain long before Parker Brothers purchased it, so the toy company’s trademark claim on the game couldn’t stand. The case dragged on for ten years and nearly bankrupted Anspach, but eventually made it to the Supreme Court. In the end, Anspach won the right to trademark the name “Anti-Monopoly” and the suffix “-opoly” (which Parker Brothers and its parent company, General Mills, had previously prevented other game makers from using). Anspach’s efforts revealed the true history of the game and opened the door for future parodies of the Monopoly brand including Duckopoly and Beaveropoly.

A Complex Legacy

Lizzie Magie wasn’t wrong about how a game about real estate could shape the way Americans view capitalism—but she probably hoped for a different outcome. After all, what began as a critique of monopolistic power has transformed into a celebration of wealth accumulation and financial dominance.

Over the past century, Monopoly has taught generation after generation about investing and strategy. The game has subtly (and not so subtly) shaped our views on wealth, property ownership, and financial success. In many ways, Monopoly holds a mirror up to society, highlighting our fascination with money, risk, and the pursuit of success—especially when it means crushing the competition. To this day, Monopoly remains a fascinating case study of how games can influence our thinking about economics, competition, and wealth.

As Magie herself said, “It might well have been called the “Game of Life,” as it contains all the elements of success and failure in the real world, and the object is the same as the human race, in general, seem to have, i.e., the accumulation of wealth.”

Want to learn more about the history and fundamentals of banking?

- Check out our article on how to kickstart your savings for National Savings Day.

- Learn how Maps Credit Union got its start—almost 90 years ago.

- Discover what those blue NCUA signs at your local branch mean.